“I feel forgotten,” The Struggles of Virtual Learning

February 4, 2021

“I feel forgotten.”

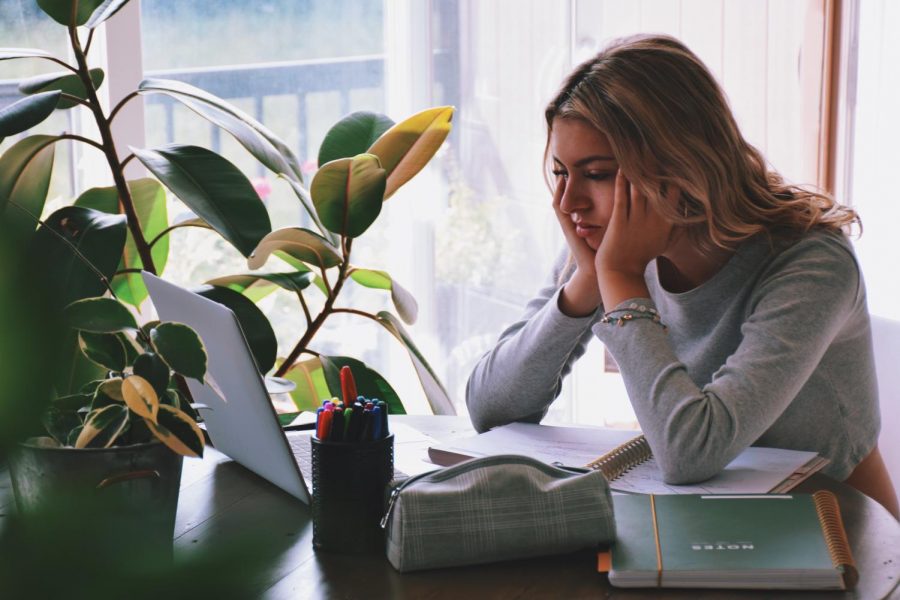

Confined to her bedroom, the walls of her home became a cage. A well furnished one, with access to a constant supply of food and warm clothing, but a cage nonetheless. With the price of an extra half an hour of sleep and a comfortable bed came isolation, the complications of technology, and a workplace shared with children. However, junior Tatiana Moreno’s struggles did not end there.

“People online are left out a lot,” Moreno said. As the Swivl became increasingly onerous, teachers were forced to balance two drastically different forms of education and virtual students received a view of a wall or a powerpoint already accessible to them via Google Classroom.

Many students are indifferent to the divide between virtual and in-person learning, but the few who rely on interaction to guide their education suffer. Riven by seclusion, Moreno is the recipient of constant unintentional reminders that her return to campus will not occur anytime soon. Any possible solution to how she and others feel has either already been attempted or is too ambiguous to grasp.

Interfering with the ability to focus comes stress and mental health, but also the addition of one commonly forgotten factor: detachment. One of the most recurring arguments of detachment is that students bring it upon themselves by choosing to turn off their cameras— when there are a variety of reasons why this may occur other than fear of appearance. Switching on cameras exposes a portion of the individual’s house, their private space, to all other students. Those in low-income environments with many siblings and a cluttered home face shame and embarrassment. (However, participation is crucial in learning regardless, and online students should never use their virtual status as an excuse to not participate in group discussions or chats.)

The separation between both sides of education becomes more prevalent when other aspects are considered.

“The average student who is typically a B/C student will not submit work on a consistent basis on a level far more drastic than with in-person learning,” a Combs teacher said. “These students tend to have D/F marks in their classes via virtual learning.” However, students who exemplify high levels of motivation show signs of perseverance no matter the situation.

“Virtual learning widens the gap between the unmotivated and the intrinsically motivated.” But this is only one facet out of the many.

Teachers who desperately strive for participation from their students feel powerless with no control over their levels of motivation, nor of their home environments. Moreno’s family specifically demonstrates a cycle of endless efforts at home.

“My younger brother and sister struggle so much, I’m always worried about them more than my own health,” Moreno said, “I’m forcing myself to get better grades while taking care of myself, trying not to push family away.”

Screams from her younger siblings when they are “extremely frustrated” reach her ears. Moments which require undivided attention, such as exams, are suddenly much more difficult to handle. And this eventually eats away at the psychological well being of students, to a severe degree.

Moreno agrees, “My mental health is definitely at it’s worst.”

“I was about to just give up completely. But there is one teacher that helped me with a simple comment,” Moreno said.

“Mr. Bunch, he told me he was really proud of me for turning my stuff in and getting a good grade. I have been so down and I felt like everything I was doing was for nothing but that comment helped me get my thoughts together and just keep working.”

Masked behind sufficient grades may be a student collapsing under stress.

The cage of walls is suffocating to some, Moreno was trapped within it. But she found an escape, a little motivation.

Though there is no clear answer to lessening virtual complexities and improving participation, a simple “you’re doing great” could be the only thing they need to help guide them along the correct path.